Book Review

2023-02-xx

by Darknut

Labyrinth: The Adventure Game

2019 by River Horse

Verdict:  Very accessible despite its flaws.

Very accessible despite its flaws.

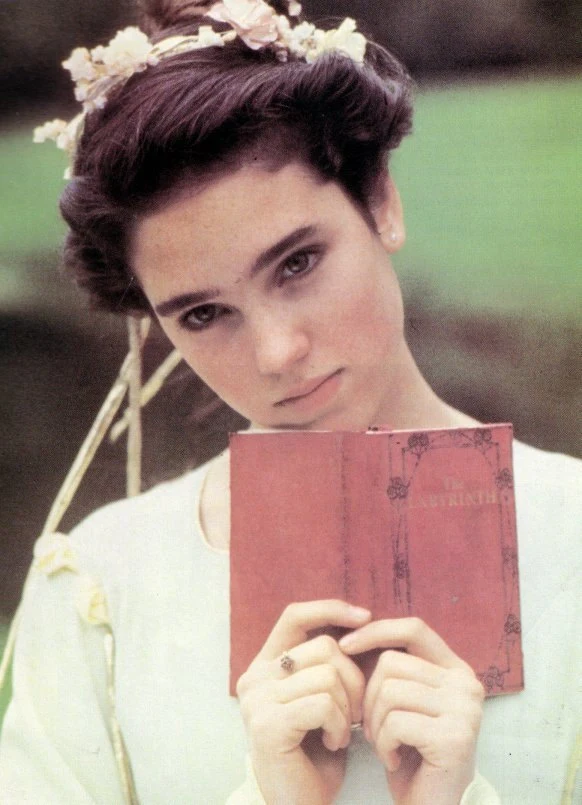

The book is actually a little bigger than this.

The book is actually a little bigger than this.Warning: If you haven't seen the Jim Henson Labyrinth movie, or if you don't like it, either because it was too silly or because you couldn't stop looking at David Bowie's crotch, then go ahead and close window.

I'm interested in novel table-top RPGs with rules tailored to facilitate reenacting the source material, or at least ones with rules I can agree with... So, at some point in the past, I discovered that a game based on the 1986 Labyrinth movie has been published. I don't remember exactly why I wasn't very interested at the time; maybe it just seemed too gimmicky. Notably, a rectangular hole has been cut through all the pages of the book in order to store a pair of dice there. I guess this is supposed to be "cute", but it seems like a waste of an awful lot of page area and perhaps a risk to the structural integrity of the book, an extra way in which the book could be damaged. Also, these dice have "the owl" in place of the 1 pip, and I think of this as a distraction. This all indicates the book is meant for newbs, and maybe that's all it takes nowadays for me to close window.

But for some reason, I'm interested now. Somewhere I learned that the majority of the book is adventure content, which is potentially very important to me, and the best part is that every "scene" provided, roughly equivalent to a scene from the movie, is presented within exactly two pages. There are 99 of these "scenes", and each one is described more or less completely within its two pages, which facilitates turning to the one you need during a game without too much preparation. Only about a third of the scenes will be visited in a play-through, most chosen randomly, so there is some implicit opportunity for variety if the game were to be played again. (If this were a videogame, the term "replayability" would be used.)

I now think the hole through all the pages isn't that big of a loss since the book already fills every empty niche on the pages with clippings of Brian Froud artwork. A bit of asymmetric quirkiness is appropriately part of the theme. On the other hand, the dice will fall out of the book the instant you begin flipping through the pages. The internal space can only be used for long-term storage.

The target audience is roughly the same as for the movie, so the players would have to be kids, or kids-at-heart, or it could be a group of more serious RPG players who feel like taking a break from being ultraviolent murderhobos, etc.

I still had to read some reviews before I could buy this thing. I will be quoting one review written by "The Wyzard" in particular that was most insightful. It makes some important points, starting with the book's cover:

It also includes color author photos on the inside front. I cannot recall another TTRPG that does such a thing, and so the dustjacket loses points for hubris.

That is correct. Look at these two pretentious assholes. But it's also true that if you remove the dust jacket, the cover underneath was deliberately made to resemble the Labyrinth book that Sarah consults at the beginning of the movie. It's pretty small for an RPG book, but OK, that's cool.

The book begins by introducing the concept of an RPG in a flurry as though the author can't help but mention things out of order in his excitement — though this is traditional. The rules are arranged so most topics also fit within two pages each, which is appealing.

But you may notice immediately that this is one of those "self-published" books that didn't have an editor:

There's a sharp change in authorial voice here, as the sections of the book were written by different people.

The book is full of grammar errors, and the relentless shifts in writing style don't help. Roll to see how you react. The roll may be improved (see page 23) if the player is also illiterate. On a roll of 5 or 6, you find the authors' whimsical grasp of English endearing. However, on a roll of 1 (the owl), you notice that the book gives somebody credit for "Proofreading" — somebody who certainly must be an imaginary construct, an unfulfilled promise to convince Kickstarter supporters that someday this half-assed project could somehow become a real book. Alas, this is the world we are all trapped in now.

Of course, it is traditional for RPG books to be self-published, and this wouldn't be the first time I thought the value of the content outweighed a shoddy presentation. It stands out notably in this case because some aspects of this production are fantastic, which leaves the rushed parts all the more noticeable. Jim Henson's posthumous name is on the cover, which sets some expectations, and Brian Froud's artwork is inside, although it's mixed with other artwork that seems so unnecessarily mediocre that it's rude to even be in here, as if they somehow couldn't locate a supplementary artist besides a close friend. The entire book is printed in some degree of color, and there are frilly borders in all the margins and not one, but three ribbon bookmarks, which help to purport that I'm holding a precious artifact, yet I find some downright lazy Photoshopery in some areas, like I'm just not supposed to care to look too closely or something.

Then we get to character creation, which is fine until you realize you have to select a race. You can be a human visitor, of course, but you can also be a Hoggle, a Ludo, a Sir Didymus, or even a tiny Worm. Or rather, you can be a "kin" of those creatures. The game takes the characters in the movie and posits that each was merely one of a whole race of similar creatures:

In Star Wars, we saw one Hutt in the movies, Jabba, and he was a crime lord and he was this unique figure. The EU, in extrapolating from the films, made Crime Lord the natural role of Hutts in the galaxy for reasons of shallow emulation. Jabba was no longer exceptional or exotic, he was presumed to be the standard archetype because we had never seen another Hutt. Ludo was a sui generis creature in the film. There's no reason to assume he was typical of a kin, or that there was anything else like him at all. If there were other Horned Beasts, there's no reason to assume they were all that large or that they all possessed a typed psychokinetic ability.

There's no reason for Didymus' status as a knight (his obsession with honor and chivalry, etc.) to be linked with his physical configuration. "Knights of Yore" strikes me as a calling, not a species, chimerical though they may be.

It's unfortunate that this taxonomy need be imposed on such unique holotypes. Many NPC creatures are also categorized this way later in the book. But on the other hand, how else can the game present the kinds of characters players should like to play? A game like this can't help but try to make the world of the movie "broader" so as to allow characters like those in the movie but that players could call their own. Correspondingly, the game necessarily implies that other human visitors besides Sarah have become lost in the Labyrinth. At least the game does say your character could be anything else you can think of that would fit in.

Each race has some advantages or disadvantages, but power-gamers will quickly identify the exploitable choices. I immediately see that I will be adding some House Rules to make the choices a little more balanced.

The character sheets are presented in the midst of the book, with the rectangular hole clumsily punched through them, which is perplexing, plus you'd have to wreck the binding if you wanted to photocopy them. I guess you're just supposed to take them as a preview of what you might be allowed to download from the Internet and print out later. Some fields don't offer enough space, while a dubious "notes" area dominates the middle of the sheet. It's as if the authors had never designed a character sheet before and/or didn't actually playtest this thing. Since the necessary details of a character in this game are so minimal, it would be easy for you to form your own character sheets or just use blank paper or index cards.

This is an adventure module that happens to include a system you can use to play it. You could likely use other game systems you happen to be fond of if you preferred, and were willing to rejigger things just a bit.

That's a fair way to put it. For an RPG, this game barely has any rules, and the book repeatedly recommends that you change the rules if you wish (which is somewhat of a copout). Apparently some players may find this lack of structure uncomfortable, but for me, it's liberating because too many rules can distract from the type of experience I want to have.

Challenges are asymmetrical in that rolls are only made for the players; the NPCs don't get equal treatment. There's no combat system. There isn't a way for anyone to really get hurt or die. But really it couldn't be any other way to reenact the movie. Instead of focusing on the details of battle, this game focuses on dealing with wacky characters and puzzling situations.

The game maintains the same mixture of creepy and silly as in the movie, and this carries over to the stakes that replace the threat of death in other games. For example, there are a few places where you could magically lose a friendship, or a personality trait, or your memory, or otherwise get transformed for possibly the rest of the game. Yes, you can fall into the Bog of Eternal Stench; there is a table to roll on to determine which kind of stench you get. Sometimes these risks sound like they could almost be worse than death, or at least they're disturbing enough to pique the imagination, and I think this is the way a Labyrinth RPG should be. Of course, the overriding threat is the risk of running out of time to solve the Labyrinth. Players lose time due to unlucky rolls while exploring, but also their choices are often subtly important. A helpful ally made or lost by the player early in the game will likely reappear later.

Many "random" objects can be found along the way. This almost makes the game feel like an adventure computer game from the 1980s except that most of the objects have no specific predetermined uses. The game usually doesn't require that each challenge must be overcome in a particular way; it's left up to the players to invent a use for abilities or items in their possession, and it's up to the GM to improvise constantly. In some other games, I'd find this loose interpretation of characters' abilities to be inappropriate, but I think it fits the whimsical setting here fine. Some situations are easy to pass while some may seem impossible depending on the group of players and what they happen to have at hand. But if an obstacle seems "not fair", the Labyrinth always allows the players to backtrack and try a different way.

Some challenges require the physical participation of the players rather than their characters. For example, at some point the players might be prompted together to mimic the "Helping Hands" scene from the movie. Some of these are fun ideas but wouldn't work as stated if you were trying to play this thing remotely. Some of the challenges are literally puzzles on a board or riddles for the players to solve, but this is probably a better RPG to shove that sort of thing into than most others.

From the GM's perspective, the detail in which each situation is described varies drastically. Some are comprehensive and quite clever; some are so vague or even contradictory that they require doctoring. (If you're paying attention, you'll notice that "Guest Authors" are credited for some of the most awkward scenes. Again, it feels like someone should have taken ownership of the book as a whole in order to better unify all the differing ideas.) It's OK if you think of everything as "idea seeds" that you should expect to modify. Very few "stats" are provided, but since every challenge is 1D6 versus a difficulty number, the space in which the GM has to make things up on the fly is pretty manageable.

Likewise, the sincerity of everything presented that wasn't in the movie varies drastically, but again, there's nothing stopping you from fixing the things you think don't belong:

This is not a setting book. It does not tell you why Jareth or someone else is the Goblin King, or what is the relationship between the Goblin King and the Labyrinth and the goblins, or what any given Goblin King might want to steal from mortals or why they might want to steal it.

The game contains a few easter egg references to some of the Labyrinth-inspired comics, but it avoids saying anything about them. I wouldn't say that it adopts any of them as canonical, of course, as it shies away from developing any kind of canon.

Indeed. Some background topics yearn to be discussed, though I suspect the authors deliberately left things open-ended so as to please the broadest range of fans — by not forcing everyone to accept the Expanded Universe while simultaneously making coy references to it. Possibly the best move available.

There are a few full-color glossy pages in the back that include stills from the film, as a sort of gallery. My dudes, we have already seen the movie, that's why we bought this game. Even a few pages of textual engagement with the premise would have made this a much more interesting book.

Again, that is correct. "The Gallery" at the end serves zero purpose because nobody is going to play this game without watching the movie — probably not without having just watched the movie. Failing to meet this prerequisite is implausible. So yes, practially anything would have been a better use of these pages. Personally, I'd like to have seen a "bibliography" of Expanded Universe sources. Detached handouts or character sheets could have been nice, too. Maybe a page or two giving the GM some guidelines for how difficult to arbitrarily make things for the players, or a couple pages suggesting how to tie together some recurring themes and characters that are otherwise mentioned only in passing, their significance hinted at but left unspoken.

Overall, this book is a plentiful buttload of "idea seeds" for encounters that do a pretty good job of capturing the tone of the movie and expanding upon it in acceptable ways. Cases in which the Labyrinth Expanded Universe being presented here are wrong will nonetheless inspire you to correct whatever is wrong on the spot. Some of the proposed scenes are wonderful, and I keep thinking about fun ways to improve or personalize what's here. Some aspects of the book are embarrassingly sloppy, but it's admittedly good enough to work with. I would like to play this game.

Be aware that all the scenes in the game are illustrated by a rudimentary map, some more necessary than others. These maps by themselves, without GM notes, are available for download here in case you want to be able to print or display them as visual aides.